With Korea’s Hanjin Shipping filing for court receivership recently, the assumption that major container lines will always find a way to survive has been rocked, according to the latest Container Insight Report released by Drewry.

In 2009, when the container industry posted operating losses of nearly US$20 billion and many lines were said to be minutes from bankruptcy, none died. The “zombie” carriers’ survival methods were varied and complex, ranging from off-hiring ships to requesting government support, but ultimately they worked.

Having survived the worst crisis the industry has ever faced the assumption grew in strength that major carriers could not be killed off. While some smaller players have fallen by the wayside this decade none were remotely in the same league as Hanjin Shipping, which with a containership fleet of around 100 ships and total capacity of 620,000 TEU ranks it seventh in the world.

Hanjin’s move into administration shatters the complacency that major carriers are immune to failure and can stomach prolonged years of low rates and financial losses.

Drewry believe that the container industry is hardly in rude health but Hanjin, along with compatriot Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM), stood out as being in particularly bad shape.

Both carriers have occupied the lower reaches of Drewry’s Z-score freight operators’ financial stress index for some time and as of the mid-way point of 2016 had readings well below 1.8, indicating a higher risk of bankruptcy.

Since then, HMM has successfully negotiated a huge debt restructuring plan, including obtaining reduced charter rates from ship-owners that eventually saw its main creditor, the Korea Development Bank (KDB), become its largest shareholder.

It will join 2M carriers Maersk Line and MSC in a new alliance next April, assuming regulatory approval.

The KDB is also Hanjin’s main creditor, but its self-rescue plan has not proceeded as smoothly as over at HMM.

Vessel charterers, most publically Seaspan, refused to lower their rates, and despite selling a number of assets, the plan to sell two tranches of new shares to sister company Korean Air fell short of raising the sums expected by creditors.

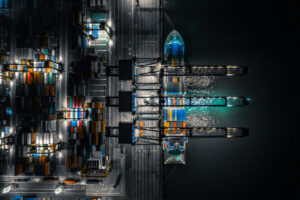

The immediate collateral damage of Hanjin’s situation will be widespread. Ports and terminals that have recently accepted Hanjin ships and containers will not only lose a customer but might not get paid for work carried out; the same applies to container lessors, and charter shipowners, particularly Seaspan and Danaos, which were Hanjin’s biggest suppliers of non-owned ships.

Given the parlous state of the time-charter market at present those companies will struggle to fix those ex-Hanjin rented ships at anything like the same rate.

Dr John Coustas, CEO of Danaos, said: “We are disappointed that the Korean Development Bank has failed to support an important participant in the global containership business.

“Danaos actively supported Hanjin in its efforts to restructure its operations and we are hopeful that Hanjin will be able to achieve a restructuring of its business and emerge from court receivership as a financially stronger company.”

Even shippers unaffected by Hanjin’s situation will feel a short-term shock as the reduction of capacity will inflate freight rates.

Notwithstanding the general rate increases (GRIs) already in-place freight rates out of Asia surged the day after Hanjin’s announcement.

Then there are the various service partners with slots onboard Hanjin ships. The carriers facing the biggest disruption are Hanjin’s partners in the CKYHE Alliance – Cosco, K Line, Yang Ming and Evergreen – who operate a number of services in the East-West container trades.

Many shippers will be unaware that when they book with carrier Y that their container will actually have been moved on a Hanjin-operated vessel.

Hanjin’s service partners will have already started efforts to arrange alternative shipments but there will be inevitable delays, especially for containers stuck on ships denied entry to ports.

There are also longer-term implications. The CKYHE Alliance will have to fill in the gaps caused by Hanjin’s exit, which is likely to disrupt their network scheduling for some months.

Also, Hanjin was due to leave the CKYHE Alliance next year as part of the reshuffling of carriers into new groups and form a new pact with Hapag-Lloyd, K Line, MOL, NYK and Yang Ming called THE Alliance.

Hanjin’s impending exit immediately puts this grouping on the back foot, erasing any pre-planning and meaning that it will be diminished in size in comparison to 2M + HMM and the Ocean Alliance (CMA CGM, Cosco, Evergreen and OOCL).

Perhaps the most far-reaching consequence of Hanjin’s situation, alongside the recent defensive M&A activity, will be that all stakeholders will now finally understand that carriers cannot survive on a diet of ultra-low freight rates if they want to see healthy competition.

The Drewry View: The impending bankruptcy of Hanjin should serve as a warning that carriers do have breaking points and that they will not always be rescued. Unless shippers make the altruistic decision to pay more to save carriers (unlikely) they will need to pay more attention to the warning signs.